The film opens with the dramatic massacre of the Armenians in Stavros’ village in central Turkey. The Sultan has ordered empire-wide killing of Armenians in response to a group of activist Armenians who have taken over the Ottoman Bank in Constantinople (now Istanbul) in a desperate effort to get the European Powers to intervene to stop the Sultan’s massacres of the Armenian population in the previous year. As the local Ottoman officials deliberate over the orders from the Sultan in their bureaucratic chambers in a provincial Turkish town, Kazan’s mise-en-scène has all the meticulous detail of his best interior social and cultural settings.

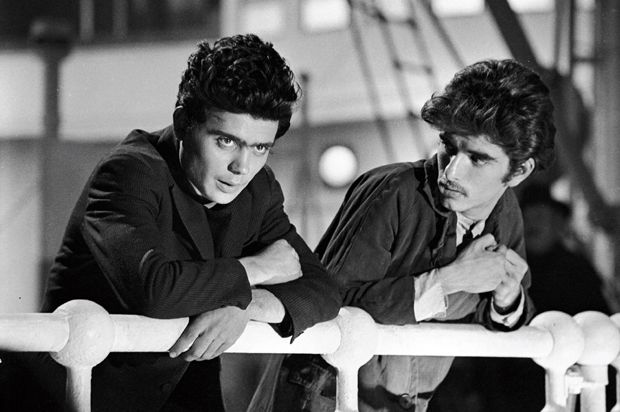

The Dance of Vartan. «America America». 1963

From there, Kazan creates scenes of a terrorized Christian village in Turkey. We watch from an aerial perspective as the doors and shutters of houses and stores are shut and slammed as Armenians and Greeks run through the streets in terror. In the film’s black-and-white, shadows and glaring light create a surreal-like feel.

A still from «America America» (Warner Bros. Entertainment)

A still from «America America» (Warner Bros. Entertainment)

We see the Armenian population flocking to their church for protection. Kazan captures the terror in the faces that are running, watching, hiding. In an extraordinary scene that depicts this kind of mass killing, perhaps the first such scene in a Hollywood film, Kazan’s depiction of Armenians being burned alive in their formidable church in the center of town brings together political realism with an expressionistic aesthetic that recalls «On the Waterfront» or «East of Eden». In a darkly lit scene at the local raki club a man shouts, «It’s beginning!» and we understand that the massacring of Armenians has a ritualistic aspect to it — and the local population has been waiting for the sign to be given.

Kazan then cuts to the inside of the church where Armenians are congregated, as candles and incense cloud the interior, and a priest leads them in prayer. The Armenians in the church are chanting (in Armenian no less) «Devormyah» («Lord have mercy»). Then there’s a cutaway to Turkish gendarmes surrounding the church, carrying torches and brush; then a cutaway to the interior of the church, where men, women and children are singing as the church fills with smoke and the icons and crosses and altar are enveloped. Outside, a priest is humiliated; he fights back, and a gendarme puts a lit torch in his hand and throws the hand of the priest into the burning church.

As flames engulf the church, we watch smoke fill the narthex; the sound of Armenian words and the screams of the dying dissolve into flames; we watch some people escape, and then Stavros’ best friend Vartan is embroiled in a fight to defend his fellow villagers. Then images of smoke and fire are juxtaposed in such a way that the scene swirls and fades to a vortex of flame and black sky, and the music crescendoes in an atonal flourish.

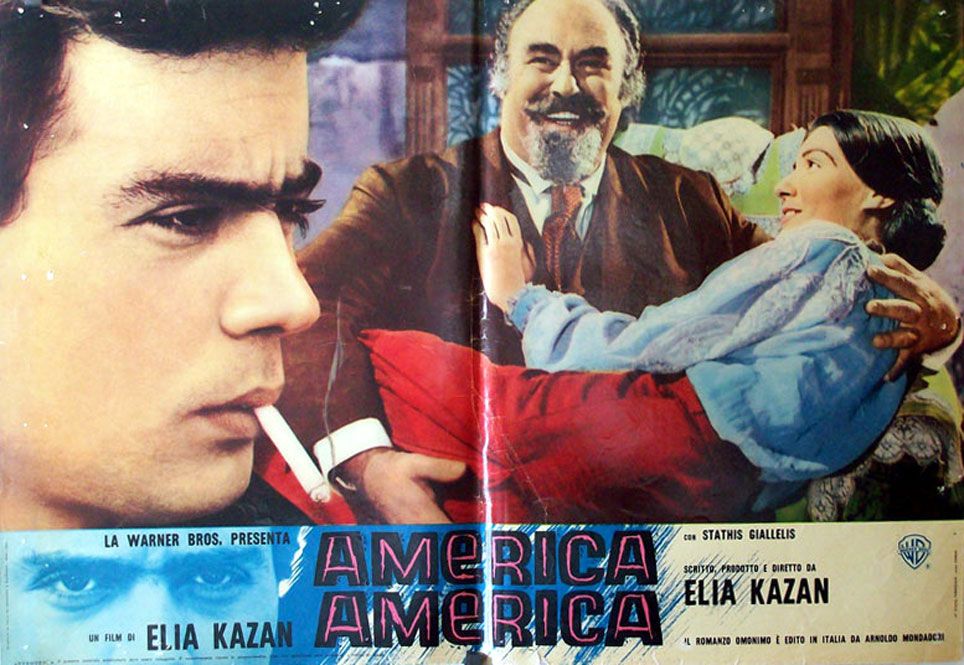

«America, America» movie poster

When Kazan cuts to the smoke-covered remains of the church, the dead are scattered in the streets; it is like watching the images of aftermath and ruin we have become accustomed to seeing on our screens. Then we see Stavros sitting next to Vartan’s corpse. Few scenes in the history of film at that time gave us such insight into the dynamics of state-sponsored mass killing, human rights atrocities and assaults on a targeted ethnic group.

After witnessing the Armenian massacre, Stavros’ family decides to send him, with all the family’s wealth, on a perilous journey across Turkey in order to take passage to America. The film then becomes one of the great bildungsromans in film history. Stavros’ journey is brutal; his initiations into violence and corruption are many, and his journey remains intertwined with various Armenians who continue to be sources of agency for him on his voyage to the land of freedom.

I have no idea if Kazan knew that the Turkish government succeeded in stopping MGM’s production of Franz Werfel’s best-selling novel «The Forty Days of Musa Dagh» in 1935 by coercing FDR’s State Department; «The Forty Days of Musa Dagh» would have been a film that portrayed the Armenian genocide with historical drama at a timely moment. Whatever Kazan’s knowledge of Turkish interference with intellectual freedom in the United States was, he did have a keen knowledge of the massacres from his family. «One of the first memories I have», he said in an interview, «is of sleeping in my grandmother’s bed and my grandmother telling me stories about the massacre of the Armenians, and how she and my grandfather hid Armenians in the cellar of their home».

Kazan’s explorations of history and corruption, of human violence and resilience, were insignias of some of his greatest films. «A Gentleman’s Agreement» (1947) was a daring exposé of anti-Semitism in American culture; «On the Waterfront» (1954) was a story of an individual’s heroic resistance to mob corruption and labor union struggles among the dockworkers; «A Face in the Crowd» (1957) was a dark portrait of a megalomaniac con artist and his manipulation of mass media and advertising culture, and the soulless terror of that culture. But «America America» took Kazan’s passion for probing institutions of human violence to a new place and a new historical reach.

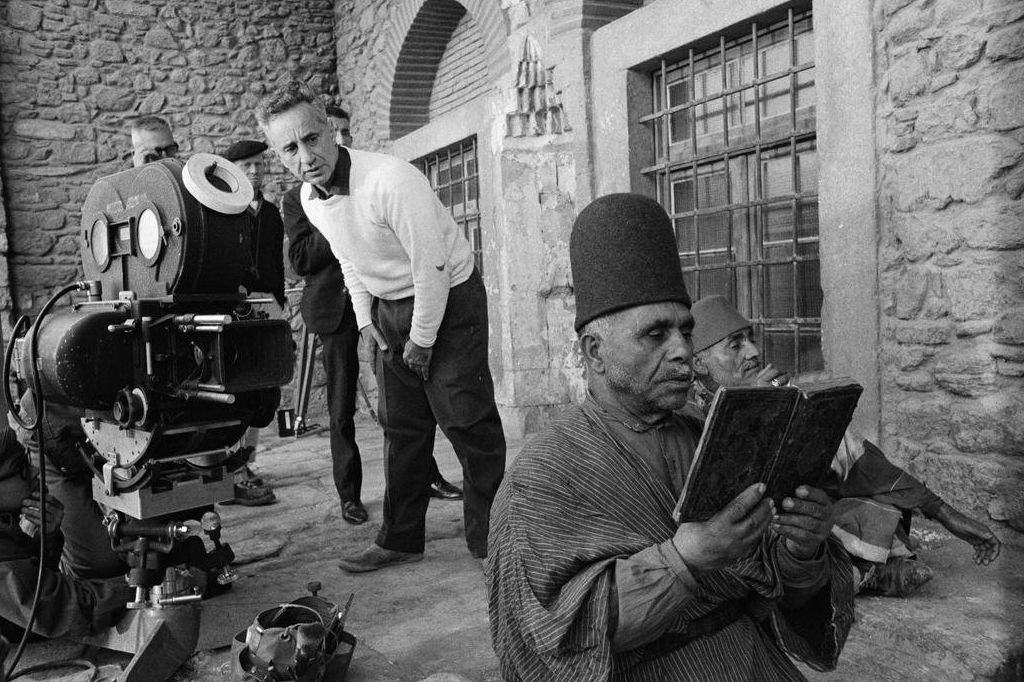

Elia Kazan on set of «America America». 1962

Elia Kazan on set of «America America». 1962